Vol. 3 – The Difference Between Anger & Abuse: Coping with Anger in Healthy Ways

Hopefully Helpful Hints for Parents, Caregivers, Educators, Counsellors, and Other Helpers When Reading This Book to Children

- This book is not a replacement for counselling services. If the child you are reading this book to is struggling with their thoughts and feelings regarding the issues in this book, it may be useful to seek out help from a qualified children’s counsellor or play therapist.

- Practice reading this book before reading it to a child. What questions do you think the child may ask? How might you answer?

- Give yourself enough time to read this book to a child. This book may bring up questions that require time for reflection. It is important to allow enough time to look at the images as some children are visual learners and this will help them to remember the content of the book. It is possible that the child you are going to read this book to may prefer to read the book in smaller chunks as well. Please do your best to follow their lead. There are also activities at the back of this book that will take some time to complete.

- Try to be a helpful listener. Helpful listening skills include:

- Listening instead of trying to think of a response while the child is talking. Use the silence in between the child’s statements to come up with your reflections.

- Reflect back what you think you heard them say. Often children will tell you if you have heard them accurately. An example of this is if the child said, “I wish I could talk to my uncle but he died. I want to tell him that I won my big soccer match,” you might say, “You miss having your uncle around to tell him about the things you are proud of.” If your reflection is incorrect, the child will often correct you and then you can try to give a more accurate reflection

- Give silent moments a chance. Embrace the silence. Silence provides an opportunity to come up with thoughtful responses and reflections.

- Be patient if questions get repetitive. Children will often ask the same question. They are trying to make sense of this new information in their brain. Help them out by repeating the same developmentally appropriate answer you gave before.

- Use developmentally appropriate language and examples in your reflections.

- Ask open-ended questions. Once the child has had time to express their thoughts and feelings and you have reflected them accurately by using your helpful listening skills, then perhaps ask a few open-ended questions. An example of a closed question would be, “Are you angry about how your friend pushed you down?” An open-ended question would be, “How do you feel about your friend pushing you down?” A closed question only leaves the option for a “yes” or “no” answer. An open-ended question will get you closer to the true feelings of the child.

- Try not to ask questions starting with the word “Why.” This may make the child feel like they have to defend their feelings. Think of how different it would feel to be asked, “Why did you push your classmate?” versus “What made you feel like pushing your classmate?” The second question will, most likely, make the child feel less defensive and will bring forward an opportunity for a bigger discussion on what makes the child miss his or her loved one.

- Try to avoid giving advice. Once you are done 1) reading the book, 2) being a helpful listener for the child’s thoughts and feelings, 3) reflecting the child’s thoughts and feelings, and 4) asking open-ended questions, then 5) this is where you could ask if the child wants to brainstorm ideas on ways to help them feel better. If the child says they are not ready to do so, respect this and do not attempt the brainstorming session at this time. What I have heard from people who are grieving is that sometimes they do not want to be taken out of their feelings. When further opportunities arise, ask if the child is ready to brainstorm ideas. Try to give options instead of advice. Let the child come to his or her own solutions. This will help build up the child’s self-esteem in decision-making and lead to the child feeling more capable of coming up with solutions to their problems.

- Normalize feelings. Share memories with the child about times you have been in a similar situation; how you felt at the time and perhaps how you feel about it now. These memories must be shared in an age-appropriate way. Make the memories short and to the point. Make sure that the focus remains on the child’s thoughts and feelings.

- Allow children to feel their feelings, even the uncomfortable ones. I have had many children tell me that an adult told them “not to cry” or to “toughen up.” It can be uncomfortable to watch a child, in pain, with sadness which can lead to statements like “dry those tears.” Crying can be healing. Perhaps help the child find a safe place to cry and let them know that you support them in expressing their feelings in a healthy way.

- When you share your feelings about how the child is feeling or acting, try to start by using the word “I” instead of the word “you.” It can also be helpful to use words like “seemed” when you are guessing about how the child is feeling. An example would be saying, “I felt worried when I saw that you seemed upset,” instead of saying, “You made me worried when you were upset.” The second statement sounds more like an accusation and the child may feel that they have done something wrong which may cause them to get defensive.

- Pick a calm time to read this book. Try to pick a time when there are little to no distractions. Try to ensure the child is well-fed, well-rested, and in a relaxed mood before reading this book. This is not always possible, but it would be ideal.

- Expect interruptions. Children are known to puddle jump in and out of feelings and only stay in them for as long as they can comfortably manage. If the child you are reading this story seems to becomes distracted, make a note of where you left off in the story and come back to it at a later time. Try to follow their lead.

- Create future opportunities for further discussion. Let the child know you are there to talk when they are ready. Then when the subject matter arises, this would be an appropriate time to talk about whatever issue is bothering the child.

- Try your best to remain non-judgmental. The best way to get a child to open up and continue to share their thoughts and feelings is to let the child know they are in a safe environment and are welcome to share thoughts and feelings without being judged.

- Try the activities at the end of this book alongside the child. They will need your help to understand some of the concepts and will need help gathering supplies. Doing these activities together will create opportunities for more conversation about the subject and will show that you are willing to help them process and express thoughts and feelings in healthy ways.

- Try not to use silver linings. Many children and families will tell me that, after they express their feelings, it is frustrating to have someone say statements like “At least you don’t have to…” or “It’ll all work out.” These statements are typically made out of love and wanting to reduce others’ pain, but can make others feel as though their pain is not legitimate; as though it should be silenced. As hard as it can be to resist the urge to give someone a silver lining, try to instead be with the person, empathize with their feelings, and listen intently.

- Remember that people express feelings in many different ways. It is important to remember that not all people will express feelings the way you would. Since people may express feelings differently, the activities at the back of this book may not be as useful to some of the children who read this book with you. It may be helpful if you support them in finding a healthy way to grieve that feels right for them. Some ways I have seen children grieve are: talking, listening, creating stories, coloring, painting, playing, scrapbooking, movement, sewing, drawing, writing, walking or being in nature, listening to or making music, or making arts and crafts.

Self-Care for the Parents, Caregivers, Educators, Counsellors, and Other Helpers Reading this Book

It is important, as a reader of this book, to process your own thoughts and feelings about the subject matter presented in this book. Please try some of the suggestions below to help you process and express your thoughts and feelings in healthy ways.

- Find time for yourself to process your thoughts and feelings about the issues presented in this book. This should be done on your own or with other adults.

- In your everyday life do what you need to bring you feelings of calm or peace.

- Reach out for support. Perhaps you could call a trusted friend or a family member, connect with a counsellor, or join a support group.

One day, in Woodland Woods, far, far away, lived a deer named Dallas.

Dallas lived a mostly happy life. She had a dense forest to live in and plenty of grass, leaves, and fruit to snack on. Dallas was a young doe and went to school at Acorn Academy.

One day on the school playground, a classmate named Rowan the Raccoon budged in front of Dallas in the line-up to go on the super-duper-awesome-fun-times zip line.

Dallas pushed Rowan down and said, “No way, no-brain!”

At that very same moment, Ms. Amanda the Arctic Hare, Dallas’ teacher, was watering her plants on a windowsill in the classroom.

When she looked out the window to check on the children outside on the playground, Ms. Amanda saw the whole thing.

Ms. Amanda asked Dallas to stay after school to talk about what had happened.

She told Dallas there are ways to express her anger with someone that will make it easier for the person to understand and hopefully work together with you to make it better.

She talked about how it is fine to be angry and we should try our best to not hurt others, ourselves, and things. She said it is okay to be angry, but it is not okay to be abusive.

Dallas asked, “What does abusive mean?”

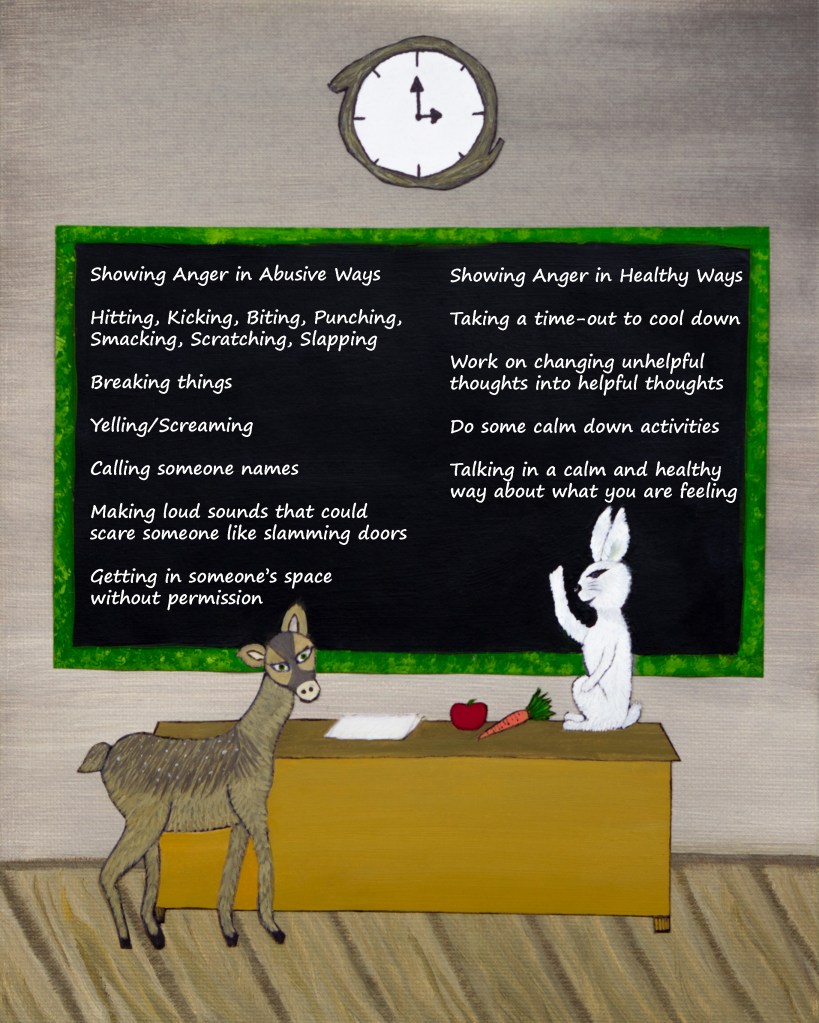

Ms. Amanda went through the difference between showing anger in abusive ways and showing anger in healthy ways.

Dallas teared up and told Ms. Amanda that she hated the feeling she got after being abusive to others.

Dallas said that after she had been mean to someone she often felt ashamed, embarrassed, and sad.

Ms. Amanda asked if Dallas would like to talk to Leanne the Long-Eared Owl. Leanne would often have a kind way of explaining why we think, feel, and act, the way we do. Dallas agreed to go on a journey to see Leanne up at the Big Birch Tree on Mindful Mountain.

Dallas and Ms. Amanda travelled together past Slippery Swamp, across the Butterfly Bridge, over Calming Creek, and beyond the Weeping Willow Tree.

They climbed halfway up Mindful Mountain and stopped once they reached Leanne’s comfy cozy nest in the Big Birch Tree.

Leanne listened to Dallas’ story and her thoughts and feelings. Then they all sat in silence for a moment or two.

Afterward, Leanne told a tale, a tale from long ago.

A long, long time ago, we had to adapt to the dangers around us.

If predators, like a sabretooth cat, came towards us, we would need to react quickly to either be prepared to attack the sabretooth cat or to escape from the danger.

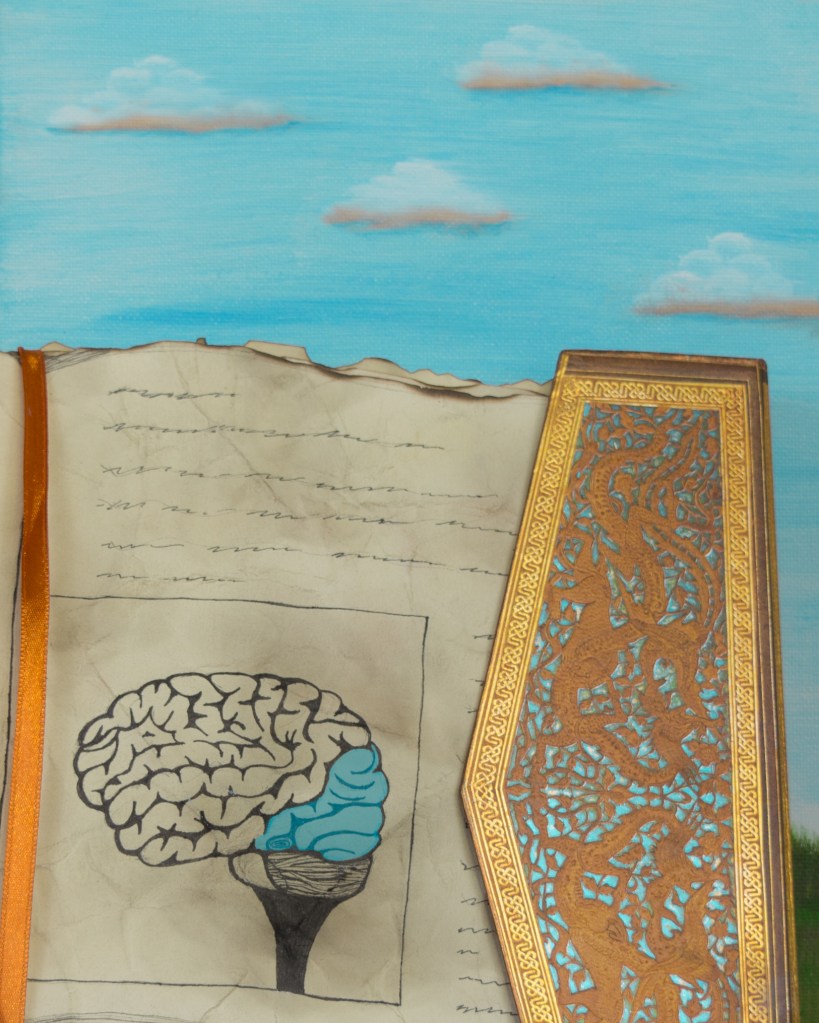

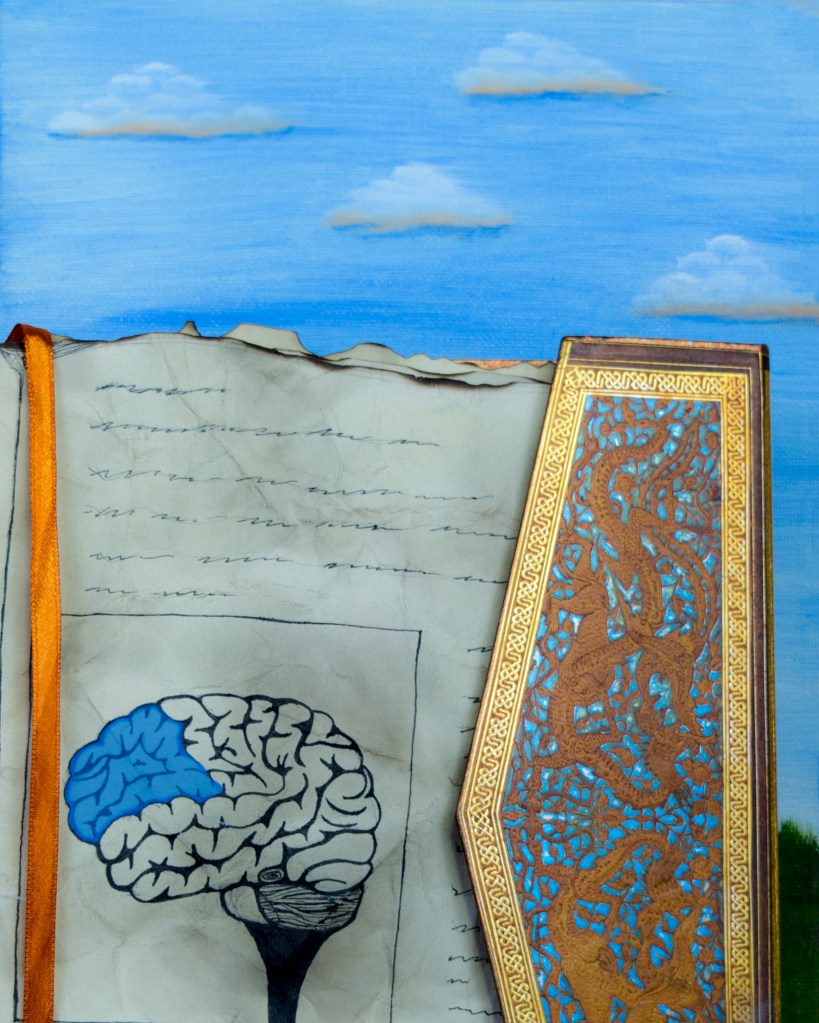

Luckily our brains developed a survival skill: we could shut down the front part to focus most of the incredible power of the brain to the back part, which is responsible for our quick reactions.

That way, we could react to danger quickly and survive.

The front part of the brain—the part that can shut down—is responsible for clear thinking, being able to see the consequences of our behaviour, and organizing our thoughts.

The brain has a hard time telling the difference between something scary (like if a sabretooth cat charges at us) and something that we feel upset about (like when our classmate budges in front of us for the super-duper-awesome-fun-times zip line).

So when we are angry or upset, we can have a harder time using the front part of our brain.

This makes it difficult to express our feelings of anger in healthy ways.

What may help to get our whole brain working together again is taking time to do something you enjoy before trying to talk about how you are feeling.

Perhaps you enjoy swimming in Lazy Lake like Tammy the Turtle and Jen the Jellyfish. Or maybe you like doing stretches like Bryan the Beaver and Lucy the Lizard.

What is your favourite thing to do to help you relax, Dallas?” Dallas replied, “I like hugs from Spike the Spotted Bobcat. I like walking by Calming Creek, and I like to frolic in mindful meadows when it is full of flowers.”

Leanne said, “The same thing happens to all brains when we are upset. It is helpful to remember that when someone we know is angry, whether it be a friend, teacher, or caregiver, it can be helpful to try to be understanding and give them time to feel settled too.”

Leanne also said, “Even Ms. Amanda and my own Long-Eared Owl family get angry sometimes. What is helpful is to always try to express anger in a healthy and safe way.

And remember, when you have been abusive, or others are being abusive to you or someone else, it is important to share about that with someone you trust. A friend, teacher, counsellor, or caregiver may be able to help.”

After speaking with Leanne, Dallas made an effort to work on learning healthy ways to express her feelings.

Dallas’ caregivers even went to see Chadwick the Chipmunk — the Adult Counsellor in Woodland Woods — to talk about their struggles in a kind and caring environment.

It took time and hard work, but the Deer family were able to find ways to show their anger in healthy and respectful ways.

Now when Dallas is upset or angry, she takes time to breathe and frolic in the meadows full of flowers to relax so she can enjoy her mostly happy life.

Until we meet again for another story in Woodland Woods…

The End

To try some activities I have found helpful to express and cope with feelings, check out the links below.

Hopefully Helpful Activities To Go Along With This Book

Here are some activities you can try to help process and express feelings in healthy ways. Hope you find them helpful!